Introduction

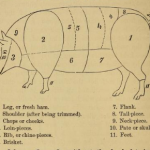

The cuts of a pig. From The Market Assistant . . . (Philadelphia, 1862)

How much does an answer to The Tea Light Question depend on the characteristics of the animal fat available? How much do the characteristics of animal fat depend on collection method?

The three little pork chops.

For this investigation, I started with three pork chops. I would dry-render one, boil another . . . and wait until I had harvested fat from those operations before deciding what to do about the third.

Chop A. The dry rendered sample

This effort was influenced by my first bouillon experiment, where dry rendering–roasting in the over–released a quantity of what seemed to be reasonably pure fat.

Chop A. Face

I heated the chop in a sauté pan placed on the stove top, without water or additional oil. Once fat began to melt I covered the pan to limit spattering. I heated the chop for about 20 minutes turning several times. The goal was not to make a tasty dinner but to collect as much fat as possible, as easily as possible.

Dry rendering was only the start of this collection experiment, of course.

…and the other side.

When it seemed that the fat was no longer melting but yes, before the meat was burned to a crisp, I removed the pan from the heat. I separated the meat from the bones and remaining pieces of fat or gristle, added all the inedible parts back into the pan with water and let them simmer for about 90 minutes. I then put the pan in the refrigerator overnight.

The sheen on the surface is fat.

Fat, bones and gristle, etc. The morning after.

The following morning, I set the pan to simmer for another two hours, then removed the bones and gristle and returned the pan to the stove top. After about 3 hours of simmering I cooled the contents in the pan, and again refrigerated overnight.

Fat collected and strained.

The next day, I skimmed the fat from the top of the pan, remelted and strained it. I let this chill then transferred the fat it to a small dish.

Chop A. Numbers

- Original weight of sample: 242 g.

- Edible portion 175 g.

- Bones and gristle removed (day 2) 33 g.

- Fat collected 16 g

- Original estimate of inedible materials: 28%

- Bones and gristle 14%

- Fat collected: 7%

Chop B. Boiling off the fat

Pork Chop B, face (above) and reverse (right)

Chop C, face

I brought this sample to a lazy boil—that is more than a simmer but not likely to boil over. After 2½ hours I removed it from the heat source and let it cool enough to be able to separate the edible flesh from the inedible parts.

I returned the inedibles to low heat for another hour then strained the liquid and let it cool overnight in the refrigerator, as with Sample 2.A. I collected the cold fat the next morning.

The collected fat, Chop B

Chop B. Numbers

- Weight of original sample 214 g

- Water used 420 ml.

- Meat removed from boiled sample 76 g

- Bones & undissolved material 71 g

- Liquid recovered 235 ml

- Fat collected 21 g

36% edible; 33% bones gristle, undissolved fat or unretrieved meat; 10% fat

Chop C. Cut to the chase

This time, I separated the fat from the uncooked sample, rendered and strained it.

Pork chop C, face

Pork chop C, reverse

Removing the fat to render it challenged a central idea in this experiment: If I remove the fat before consuming the chop, it’s not left-over. Is it still waste, or is it simply an undesirable substance? I wondered how its removal would affect the edible portions: The best way to know would be a taste test, but I’m not enough of a connoisseur of pork to have confidence in my assessment.

Experiment C. Face Reverse, and the fat removed from it.

I separated the fat from the flesh and the bone to the best of my ability. I was not able to take all of it; some small bits remained attached to the flesh as well as marbled in it. I collected some jots of flesh when I harvested the fat, too.

I processed the fat by grinding it in an electric mill with a little water; I wanted to see if this might shorten the melting time. This created a bit of a mess; next time I’ll use a knife. I placed the slurry of water and fat in a pan and heated it on a low flame. After 2½ hours there were small bits of something remaining in the pan—flesh, perhaps—but most of the fat had melted. I strained the liquid into a container and let it cool.

As I did not bother to collect much of the fat that was close to the bone, the initial quantity of fat I began with was lower than the other samples. Chopping fiasco aside, this collection method was much less messy and much less tedious than the first two..

Left: collected fat. Note the flecks of white fat in the liquid (right).

Chop C. Numbers

Initial weight of Chop C 248 g

Weight of fat removed 46 g

Fat separated and rendered 9 g

Pièce de résistance

I collected all the fat harvested from the chops, re-rendered it into one small container and added a wick.

The Candle Cam (short version)

The pork chop candle burned for about 5 minutes at a time, for an estimated total burning time of about 90 minutes. I had a problem with the wick that was probably exacerbated by the shape of the container. The light was well under a foot-candle and so more amusing than useful or even romantic. The experience has given me new respect for the Paleolithic.

Observations

Light from 21st century waste fat seems to be a lot of work for an indifferent result.

I found it difficult to collect more than 50% of my estimate of the total fat present. Some of it, yes, I ate. Some of it remained undissolved and a considerable quantity was lost to my frustratingly poor technique.

It was also difficult to collect all the fat from the liquid and it tended to go or remain everywhere I didn’t want it to be. I am the sort of person who takes a rubber scraper to eggshells but I haven’t figured out how to manage the equivalent with liquid fat. Yet.